The safety feature missing in most pre-1990 houses

Most houses built before 1990 were designed for a different era of risk, long before today’s expectations for fire protection and indoor air safety took hold. You may love the character of an older home, but behind the plaster and paneling, one crucial layer of modern protection is often missing: a comprehensive safety strategy that treats electrical hazards and hidden toxins as seriously as structure and style. Understanding what your house lacks, and how to add it without gutting everything you love, is now as essential as locking the front door.

The core promise of modern housing is not just comfort but survivability when something goes wrong. In a pre‑1990 home, that promise can quietly fray, from outdated wiring that struggles with today’s appliances to legacy materials that can release dangerous fibers or dust when disturbed. If you live in, rent out, or are thinking about buying an older property, you need to think of a whole‑house safety upgrade as the missing feature that brings your place in line with the standards newer homes take for granted.

The hidden gap in pre‑1990 homes: a modern safety baseline

When you walk through a pre‑1990 house, you probably notice the hardwood floors, the generous trim, maybe the original windows. What you do not see is the absence of a modern safety baseline, the kind of layered protection that newer building codes now assume as standard. Instead of a coordinated system of electrical safeguards, fire‑resistant assemblies, and vetted materials, you are often relying on a patchwork of legacy choices and piecemeal upgrades that may or may not work together when something fails.

Specialists who focus on renovation report that when a pre‑1990 house changes hands, the most basic systems, from the foundation to the wiring, are the ones most likely to show their age. Structural movement, including foundations, cracks, and sagging framing, is a recurring concern in older properties, and it often appears alongside aging mechanical and electrical systems that were never designed for today’s loads or lifestyles. In many of these homes, the missing “feature” is not a single gadget but a deliberate safety framework that treats structure, wiring, and materials as interlocking risks rather than isolated repair jobs, a gap that becomes clear once you start looking at home systems in detail.

Why modern codes changed the rules on safety

The reason your 1980 bungalow feels different from a 2015 build is not just fashion, it is the way safety is now baked into the rules of construction. Modern building codes are written to keep pace with advances in materials, appliances, and disaster data, and they are designed so that safety improvements move just as quickly as other innovations. Instead of leaving critical choices to chance, current standards spell out how electrical circuits must be protected, how escape routes should work, and which materials are acceptable in walls, ceilings, and insulation.

Those codes do more than add red tape. They create a shared baseline for everyone involved in residential construction, from architects to electricians, so that a new home is not just attractive but also systematically protected against fire, shock, and structural failure. With this in mind, modern building codes are now a primary tool for ensuring safety and compliance in residential construction, and they are a big part of why newer homes come with features like arc‑fault protection, tamper‑resistant receptacles, and carefully specified insulation by default. If your house predates those standards, you are living in a space that was never required to meet the expectations described in current safety and compliance guidance.

The electrical weak link: wiring that predates your lifestyle

Electricity is where the gap between old and new homes becomes most obvious. The average pre‑1990 house was wired for a world of a few televisions, incandescent lamps, and maybe a microwave, not for racks of electronics, high‑draw kitchen gadgets, and electric vehicle chargers. As a result, the circuits behind your walls may be undersized, overloaded, or simply worn out, even if the lights still turn on when you flip the switch.

Industry guidance on when a house needs rewiring now treats age as a major risk factor. In a detailed discussion of electrical safety, one analysis notes that most homes built before 1990 need a rewiring evaluation, especially those with aluminum branch circuits or other legacy components that have a history of overheating. The recommendation is not to panic and rip everything out, but to schedule a structured evaluation that looks at panel capacity, circuit loading, and the condition of connections, a process that mirrors the research methods described in the When Does a guidance. If your home has never had that kind of checkup, the missing safety feature is not just new wire, it is the knowledge of what is actually happening in your electrical system.

Knob and tube, aluminum, and other legacy wiring risks

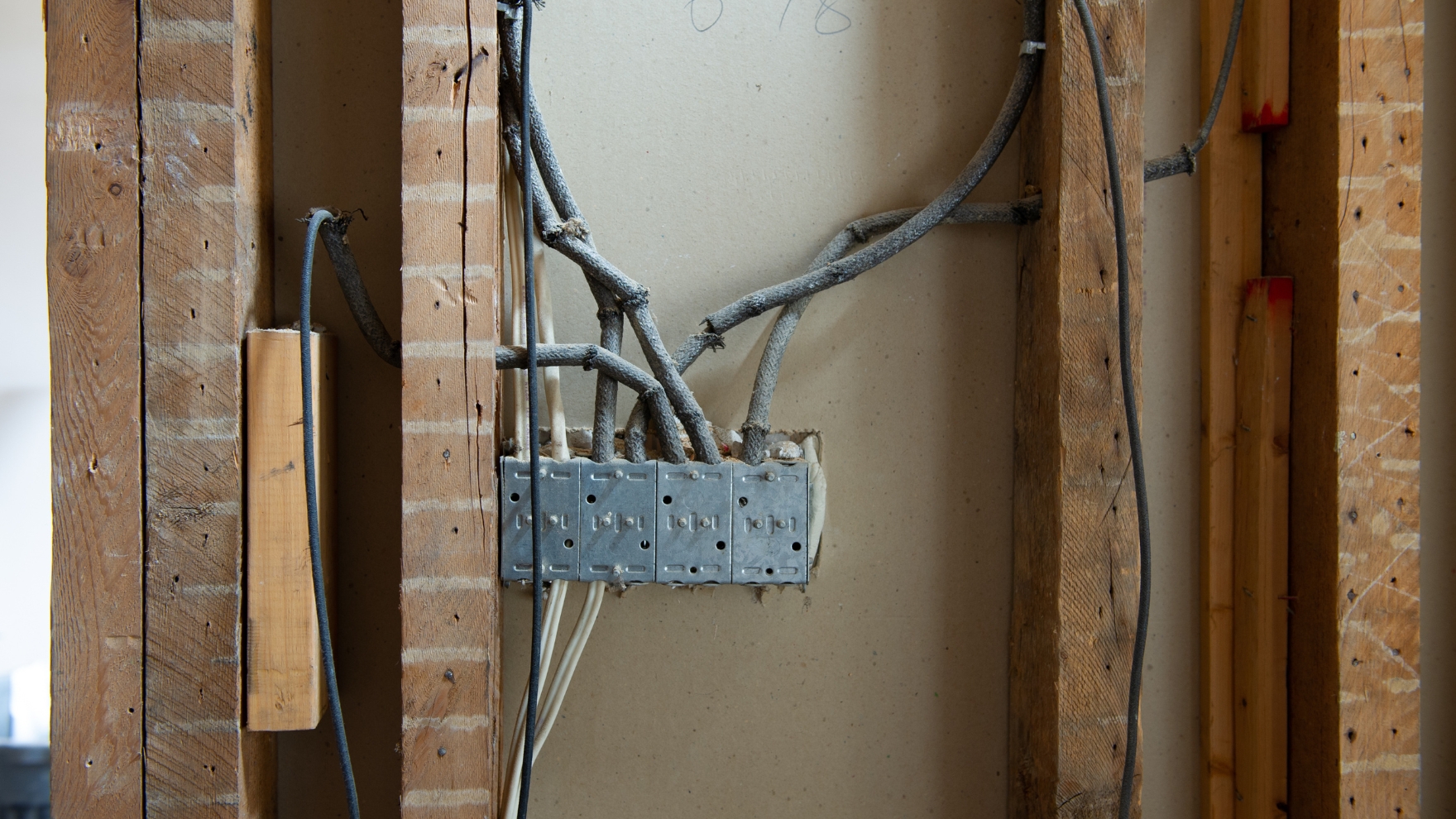

Some of the most problematic electrical systems in older homes are also the ones that hide most easily. Knob and tube wiring, which uses ceramic knobs and tubes to route individual conductors through walls and ceilings, can still be found in houses that have otherwise been updated with modern finishes. It was considered state of the art a century ago, but it lacks a grounding conductor, is often spliced in unsafe ways, and can be buried under insulation that traps heat around the wires.

One detailed review of Common Issues Found in Homes Built Before 1990 describes knob and tube wiring as “electrical nostalgia nobody asked for,” and warns that it can be a serious hazard hiding behind horsehair plaster or other early wall systems. Aluminum branch wiring, which was used in some mid‑century construction, brings its own set of concerns, including a tendency for connections to loosen and overheat if they are not handled with specific techniques and compatible devices. If your inspection report mentions Knob, Tube Wiring, or other legacy methods, you are looking at a system that predates modern expectations for grounding, fault protection, and load, and that gap is precisely why experts flag these installations as Electrical Nostalgia Nobody.

The other invisible threat: asbestos in everyday materials

Electrical hazards are only half the story in pre‑1990 homes. The other major blind spot is what your walls, ceilings, and floors are actually made of. Asbestos was widely used in insulation, wallboard, ceiling tiles, floor coverings, and even some textured paints because it was cheap, durable, and resistant to heat. The problem is that when those materials are cut, sanded, or broken, they can release microscopic fibers that lodge in the lungs and are linked to serious diseases.

Public health agencies now warn that asbestos can be found in many homes built before 1990, and they stress that you should always check if asbestos is present before you start doing any repairs, maintenance, or renovations that might disturb older materials. That advice is not theoretical. It is based on decades of evidence about how fibers behave once they are airborne and how long they can remain in a house if they are not properly contained. If you are planning to open up walls, scrape ceilings, or replace old flooring, the missing safety feature is a deliberate plan to identify and manage asbestos before you create dust.

Why professional asbestos inspections are now non‑negotiable

Because asbestos is invisible to the naked eye once it is in dust form, guessing is not a safe strategy. A professional inspection is now considered essential for pre‑1990 home renovations, especially if you are planning to remove old linoleum, demolish walls, or alter heating systems that may have insulated pipes or ducts. Inspectors take samples of suspect materials, send them to accredited laboratories, and map out where asbestos is present so you can plan work around it or arrange for licensed removal.

One case study from a renovation project describes how, during the process, the team discovered asbestos in unexpected places, including under newer finishes that had been installed over older layers. Without testing, those hidden materials would have been cut and sanded, releasing hazardous substances into the living space. That experience is part of why guidance on Why a Professional Asbestos Inspection for Pre‑1990 Home Renos is Essential now frames inspection as a first step, not an optional extra. If you are serious about safety, you treat a professional asbestos inspection as a core part of your renovation plan, not a line item to be trimmed from the Home Renos budget.

Old‑house charm, modern‑day hazards: lead, insulation, and more

As you look beyond wiring and asbestos, the list of potential hazards in older homes grows longer, but it also becomes more manageable once you know what to look for. Some of the most concerning dangers of old houses are asbestos and lead paint, especially in properties built before the government banned certain uses of these materials in the late 1970s. Lead‑based paint can flake or turn into dust, particularly around windows and doors, and that dust can be ingested or inhaled by children, who are especially vulnerable to its effects on development.

Insulation is another quiet risk. Older loose‑fill products can contain asbestos, and even when they do not, they may be so thin or patchy that they leave your home under‑insulated, which can contribute to ice dams, moisture problems, and mold. Safety tips for living in an old house now emphasize a combination of testing, targeted abatement, and practical steps like using HEPA vacuums and wet‑sanding methods to control dust. When you follow that kind of guidance, you are not just preserving character, you are actively upgrading the health profile of your home in line with modern safety tips for older properties.

What inspectors and insurers now look for in older homes

If you are buying or refinancing a pre‑1990 house, you are not the only one scrutinizing its safety gaps. Home inspectors are trained to look for patterns that show up again and again in older properties, from outdated electrical panels and missing GFCI protection to foundation cracks and signs of structural movement. Detailed inspection guides for older homes walk buyers through what to expect, including the likelihood of aging roofs, obsolete plumbing materials, and the need for further evaluation by specialists when red flags appear.

Insurers are paying attention too. When you shop for coverage on an older home, underwriters often ask about the age of the roof, the type of wiring, and whether there have been updates to heating and plumbing systems. They know that certain combinations of age and materials correlate with higher claim rates, particularly for fire and water damage. Consumer‑facing checklists now encourage you to ask about these same issues when shopping for an older home, so you can anticipate which upgrades might be required to secure coverage or favorable rates. By aligning your own due diligence with what inspectors and insurers look for in older homes, you turn a vague sense of risk into a concrete plan.

Building your retrofit roadmap: from evaluation to action

Closing the safety gap in a pre‑1990 house starts with information, not demolition. A smart retrofit roadmap begins with a thorough inspection, followed by targeted evaluations of high‑risk systems like wiring and potential asbestos‑containing materials. Detailed guides on what to expect when buying older homes recommend budgeting for follow‑up assessments by electricians, structural engineers, or environmental consultants when initial inspections uncover concerns that go beyond a generalist’s scope.

Once you have that information, you can prioritize work in a way that reflects both risk and cost. Electrical evaluations can identify circuits that need upgrading or replacement, while asbestos surveys can map out which areas must be handled with special precautions during future projects. Structural assessments can clarify whether cracks are cosmetic or signs of deeper movement. By treating these steps as the missing safety feature in your pre‑1990 home, you move from reactive patching to a proactive plan that brings your property closer to the standards embedded in modern codes and best practices. Resources that explain what to expect from older homes can help you frame that plan before you spend a dollar on cosmetic upgrades.

Like Fix It Homestead’s content? Be sure to follow us.

Here’s more from us:

- I made Joanna Gaines’s Friendsgiving casserole and here is what I would keep

- Pump Shotguns That Jam the Moment You Actually Need Them

- The First 5 Things Guests Notice About Your Living Room at Christmas

- What Caliber Works Best for Groundhogs, Armadillos, and Other Digging Pests?

- Rifles worth keeping by the back door on any rural property

*This article was developed with AI-powered tools and has been carefully reviewed by our editors.