What Caliber Works Best for Skunks and Opossums Without Overpenetrating

When you are dealing with skunks and opossums around a home or farm, the right caliber is not just about cleanly killing the animal, it is about keeping the bullet from sailing on into a barn, a neighbor’s yard, or a propane tank. You are trying to balance enough power for a humane dispatch with limited penetration and controlled ricochet risk. That balance starts with understanding how small‑game calibers behave in real backyards, not just on a ballistics chart.

Skunks and opossums sit in an awkward middle ground: tougher than rats, but far smaller and thinner than coyotes. You need a setup that delivers precise shot placement, modest velocity, and bullets or pellets that dump energy quickly instead of drilling through. With that in mind, you can narrow your choices to a handful of rimfire and airgun options that are proven on similar small animals and that give you more control over where every projectile stops.

Understanding the Overpenetration Problem Around Buildings

Overpenetration is not an abstract range concern when you are shooting at a skunk under a deck or an opossum in a tree over a fence line. A bullet that exits the animal with significant energy can punch through siding, vehicle sheet metal, or even a window before it finally stops. You are also dealing with hard surfaces, from concrete pads to metal gates, that can turn a missed shot into a ricochet. That is why you should think of these animals the way small‑game and Varmints are treated in dedicated ammunition guides, where the emphasis is on enough striking energy at moderate cost without excessive damage or unpredictable bullet travel.

In a backyard, your “backstop” might be a dirt bank, but it might also be a neighbor’s garage. That is why you should favor slower, lighter projectiles that tend to stop in soft tissue or soil rather than high‑velocity centerfire rounds that are designed to retain energy. The same logic that leads pest‑control shooters to choose smaller calibers for Pests and other small Animal targets applies here: you want a round that does its work inside the animal and then quickly loses steam. Thinking this way shifts your focus from raw power to controllability, trajectory at short range, and how forgiving the round is if your shot is not perfectly centered.

Legal, Ethical, and Practical Constraints With Skunks and Opossums

Before you pick a caliber, you need to confirm that Shooting nuisance wildlife is even legal in your jurisdiction and under what conditions. Wildlife agencies often classify opossums as furbearers or nuisance animals, but they still regulate how you can dispatch them. Technical guidance on opossum control notes that a rifle of almost any .22‑caliber or larger will kill opossums, and that a .22‑caliber rifle or pistol or a 12‑gauge Shotgun with No. 6 shot are effective tools, but it also stresses that the legality of Shooting nuisance opossums varies by state and locality, so you must check your rules before you ever load a magazine.

Ethically, your goal is a quick, humane kill with minimal suffering and minimal collateral damage. That means you should only take shots where you have a solid backstop and a clear view of the animal’s vital zone, and you should be prepared for follow‑up shots if needed. With skunks, there is an added practical constraint: a mortally wounded animal can still spray. Extension guidance on skunk control warns that skunks often release their scent when they are shot and recommends aiming for the brain, slightly above and behind the ear, while also advising you to Look carefully for light and intermittent breathing and to Err on the side of caution if you are not sure the animal is dead, because a premature approach can trigger a spray at close range.

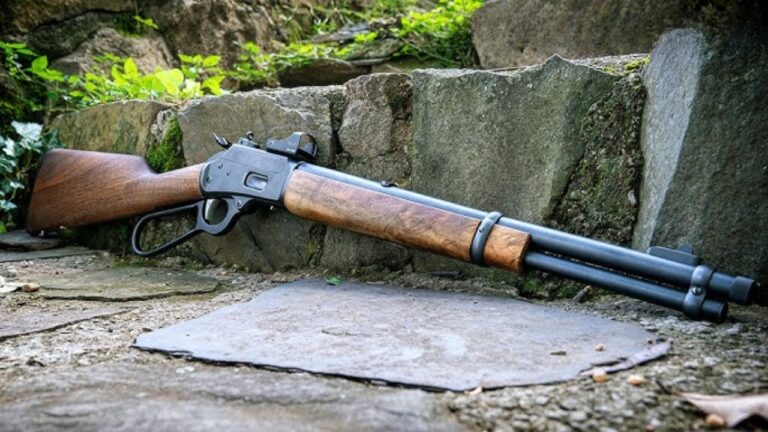

Why .22 LR Remains the Rimfire Benchmark

For many landowners, .22 Long Rifle is the default answer for small nuisance animals, and there are good reasons for that. It is widely available, relatively quiet in subsonic loads, and accurate enough for head shots at typical backyard distances. Small‑game specialists consistently describe .22 LR as a go‑to round for rabbits and similar‑sized animals, noting that it is widely considered one of the Best Caliber for Small Game Hunts when you are shooting Squirrels and other small game inside typical rimfire ranges of roughly 25 to 75 yards, which is the same envelope you are likely to face with skunks and opossums near buildings.

On a trapline, where shots are often taken at animals held in foothold or body‑grip traps, experienced shooters emphasize that Most trapline shots are only a few feet and that a well‑placed .22 will cleanly dispatch most furbearers. One veteran trapper describes favoring .22 rimfire handguns because they offer high capacity and quick follow‑up shots, which matters if an opossum or skunk is moving or partially obscured. For your purposes, .22 LR gives you enough penetration for a brain or high‑neck shot without the excessive energy of larger centerfire rounds, especially if you choose standard‑velocity or subsonic hollow points that expand and slow down quickly instead of zipping through.

Air Rifles and the Case for .177 vs .22 Calibre Pellets

If you are shooting in a dense neighborhood or inside a barn, a quality air rifle can be a smarter choice than any firearm. Modern Small Game air Rifles, including multi‑pump, spring or gas piston, and pre‑charged pneumatic (PCP) designs, are built to humanely take small animals at modest ranges while keeping noise and penetration low. PCP small game hunting Rifles in particular can deliver consistent power and accuracy, and because they fire relatively light pellets, they tend to create a larger hole in the target without the deep penetration of a high‑velocity bullet, which is exactly what you want when you are trying to keep projectiles on your property.

Within the airgun world, you will usually be choosing between .177 and .22 Calibre pellets. Detailed comparisons point out that .177 Calibre is one of the most popular and widely used options for air rifles, prized for its flat trajectory and high velocity, while .22 Calibre is known for its heavier pellet that travels a bit slower but delivers more stopping power on impact. For skunks and opossums at close range, a .22 Calibre PCP or spring‑piston rifle gives you a better margin for a humane kill with a body shot, while .177 can work well if you are disciplined about precise head shots and want to minimize penetration even further. Either way, you should treat these tools with the same respect as a rimfire rifle, because a missed pellet can still travel a surprising distance if you do not have a proper backstop.

Shot Placement and Species Differences: Skunks vs. Opossums

Caliber is only half the equation; where you place the shot matters just as much for both lethality and overpenetration. Skunks have relatively small skulls and light bodies, which makes a brain shot ideal when you can get it. Wildlife‑control training materials on skunks note that Shooting is effective but will likely result in the skunk emitting odor, and they recommend a .22‑caliber rifle or pistol or a 12‑gauge with No. 6 shot for close work. To reduce the chance of a spray and to keep the bullet from exiting, you should aim for the brain from the side, just above and behind the ear, which matches the anatomical guidance provided in extension bulletins and helps ensure the projectile expends its energy inside the skull rather than passing through the body.

Opossums are built differently, with a more elongated body and a somewhat tougher skull, and they are notorious for “playing dead,” which can mislead you into thinking a marginal hit was fatal. Technical control guidance explains that a rifle of almost any .22‑caliber or larger will kill opossums and that a .22‑caliber rifle or pistol or a 12‑gauge Shotgun with No. 6 shot are standard tools, but that does not mean you should rely on marginal body hits. For rimfire or air rifles, a head or high‑neck shot from the side is still the best way to anchor the animal quickly and keep the projectile from exiting with significant energy. If you must take a body shot, angling slightly forward into the chest cavity and using expanding bullets or heavier pellets can help limit pass‑throughs compared with hard, non‑expanding projectiles.

Choosing Between Rimfire, Shotgun, and Airgun in Tight Spaces

In a wide‑open field, a .22 LR rifle is hard to beat, but most skunk and opossum problems happen in tight, cluttered spaces. In a barn aisle or under a deck, a short .22 pistol or compact carbine loaded with subsonic hollow points can give you precise control with minimal muzzle blast. Small‑game hunters who evaluate different platforms often highlight how a bolt‑action .22 or a lightweight semi‑auto can be tailored to specific species, with some recommending dedicated Varmint models like the CZ457 Varmint .17 Cal for Best for Squirrels work, which underscores how much thought goes into matching gun and caliber to small targets. For your purposes, the same mindset applies, but you should bias your choice toward the quietest, least penetrative option that still guarantees a humane kill.

In very close quarters, a 12‑gauge Shotgun with No. 6 shot, as recommended in both skunk and opossum control guidance, can be effective because the pellets lose energy quickly after a few yards and are less likely to travel far beyond the animal. However, shotguns bring their own risks of pellet spread and property damage, especially indoors or near vehicles. That is where airguns shine: a PCP or spring‑piston rifle in .22 Calibre can deliver enough energy for a clean head shot at 10 to 25 yards with far less risk of overpenetration than a rimfire or shotgun. Your decision should factor in not only the animal and the distance, but also what sits behind and around the target, and whether you can safely absorb a miss or a pass‑through.

Real‑World Caliber Choices From the Pest‑Control Community

When you look at what working trappers and rural homeowners actually carry, you see a consistent pattern: small calibers, modest velocities, and a premium on accuracy. Trapline shooters emphasize that Most of their shots are taken at very short distances and that a simple .22 rimfire, often in a compact handgun, is enough to dispatch most furbearers cleanly when the shot is placed correctly. That real‑world experience supports the idea that you do not need magnum power for skunks and opossums; you need a controllable platform that you can shoot precisely under stress, often in awkward positions.

Online communities echo that preference for smaller calibers when the goal is pest control around buildings. In one discussion about a small caliber for pest control, a user posting under the name Sardukar333 responds to a question from Jan about Just looking for ideas by joking that an American Shorthair (standard issue cat) is sometimes the best solution, before others chime in with their experiences using .22 LR, .17 HMR, and air rifles on raccoon‑sized animals that were dead anchored in place. The thread underscores a key point: people who do this regularly tend to downsize their calibers and upsize their emphasis on shot placement and backstops, because they have learned the hard way that overpowered rounds create more problems than they solve around homes and barns.

Backstops, Ricochets, and Safe Shooting Angles

No matter which caliber you choose, you are responsible for every projectile until it stops, and that means planning your backstop before you ever shoulder a rifle. Airgun safety guidance stresses that Another way to protect yourself is to have a proper backstop so that your BBs do not ricochet or go beyond your target, recommending materials like thick plywood, stacked hay, or even a small hill of dirt to catch stray shots. The same principle applies when you are shooting at a live skunk or opossum: you should position yourself so that a miss or a pass‑through ends in a safe, energy‑absorbing surface rather than a hard object that can send the projectile off at an unpredictable angle.

Ricochets are a particular concern with .22 LR, which can skip off frozen ground, rocks, or metal with surprising vigor. To reduce that risk, you should avoid shallow angles into hard surfaces and instead try to shoot slightly downward into soft soil or vegetation behind the animal. If you are working around concrete pads or metal equipment, an air rifle in .22 Calibre or even .177 Calibre can significantly cut the risk of dangerous ricochets, because pellets deform and shed energy much more quickly than copper‑plated bullets. Combined with careful attention to your shooting lane and what lies beyond it, that choice of caliber and platform can make the difference between a controlled, professional dispatch and a near miss that could have ended badly.

Putting It All Together: A Practical Caliber Strategy

When you weigh the legal, ethical, and ballistic factors, a practical strategy emerges for dealing with skunks and opossums without overpenetrating. For most rural or semi‑rural settings with safe backstops, a .22 LR rifle or pistol loaded with standard‑velocity or subsonic hollow points is an excellent primary tool, giving you enough power for head shots while limiting how far a bullet will travel if it exits. In tighter spaces, or where noise and ricochet risk are major concerns, a quality PCP or spring‑piston air rifle in .22 Calibre offers a quieter, lower‑penetration alternative that still delivers humane kills at typical backyard distances, especially when you commit to precise head or high‑neck shots.

Your backup options, such as a 12‑gauge Shotgun with No. 6 shot for very close encounters or a specialized small‑game rifle like a Varmint‑profile .17 Cal, should be reserved for situations where you have a truly safe backstop and a clear understanding of how those rounds behave. Resources that walk through What the Best Caliber for Small Game Hunts looks like, along with detailed small‑game gun lists that highlight Best for Squirrels setups, can help you refine your choices, but the core principles remain the same: know your local laws, prioritize humane shot placement, choose calibers that limit penetration, and build in redundant safety through solid backstops and thoughtful shooting angles. If you follow that framework, you can solve skunk and opossum problems decisively while keeping your property, your neighbors, and yourself out of the line of fire.

Like Fix It Homestead’s content? Be sure to follow us.

Here’s more from us:

- I made Joanna Gaines’s Friendsgiving casserole and here is what I would keep

- Pump Shotguns That Jam the Moment You Actually Need Them

- The First 5 Things Guests Notice About Your Living Room at Christmas

- What Caliber Works Best for Groundhogs, Armadillos, and Other Digging Pests?

- Rifles worth keeping by the back door on any rural property

*This article was developed with AI-powered tools and has been carefully reviewed by our editors.