Your AC can still run fine in 2026, but repairs may depend on what refrigerant you have

Your air conditioner is not suddenly obsolete in 2026, but the rules around what goes inside it are changing fast. Whether you can keep repairing the system you have now largely comes down to which refrigerant it uses and how easy that refrigerant is to source under new federal limits. If you understand where your equipment fits in the phaseout timeline, you can decide whether to keep nursing it along or pivot to something built for the next generation of cooling rules.

Why 2026 is a turning point, not a shutdown date

You are not facing a hard cutoff where your existing AC must be ripped out in 2026, but you are entering a period when refrigerant choices start to separate affordable repairs from expensive ones. Federal policy is tightening the supply of older, higher global warming potential refrigerants, while nudging manufacturers and contractors toward newer blends with lower climate impact. That means the same repair that was routine a few summers ago could now involve scarcer refrigerant, more paperwork, and a higher bill.

Regulators are using multiple levers at once, including production caps, installation limits, and detailed tracking rules for refrigerant handling. Under 40 CFR Part 84 Subpart C Standard Regulation, for example, the Environmental Protection Agency is tightening reclamation standards and leak detection thresholds so that every pound of high impact refrigerant is monitored more closely. You feel those changes indirectly, through what your contractor can buy, how they are allowed to use it, and what they have to charge to stay compliant.

Know your refrigerant: R‑22, R‑410A, R‑32 and beyond

The first step in understanding your options is to identify what is circulating inside your system. The most common legacy blend in older homes is R‑22, often referred to as Freon in many “What Are the Most Common HVAC Refrigerants” guides, which dominated residential cooling for systems installed before the early 2010s. Newer units typically use R‑410A, sometimes labeled “Puron,” while the latest generation of equipment is shifting to lower global warming potential options such as R‑32 and R‑454B that satisfy stricter climate rules.

Each of these refrigerants sits at a different point in the regulatory timeline, which is why two neighbors can face very different repair realities in the same heat wave. If your data plate lists R‑22, you are dealing with a substance that is already out of new production and limited to reclaimed stock. If it lists R‑410A, you are in the middle of a phase down where new systems are restricted but service refrigerant is still available. If you see R‑32, you are already aligned with the low global warming potential direction regulators are pushing, and your main concern becomes staying on top of evolving safety and handling standards rather than looming scarcity.

What the R‑410A phaseout really means for your existing system

R‑410A is the workhorse of modern residential cooling, so the idea that it is being phased down can sound alarming. In practice, the rules are aimed at stopping the market from adding more high global warming potential equipment, not at forcing you to junk what you already own. Guidance on Can R‑410A HVAC Units Still Be Installed After 1/1/26 makes clear that R‑410A systems can continue to be installed from existing inventory even as new manufacturing shifts to other blends, which gives contractors and distributors a buffer period to work through stock.

At the same time, you should expect the supply of new R‑410A equipment and refrigerant to tighten as the Environmental Protection Agency’s hydrofluorocarbon phase down advances. One industry overview of the R‑410A phase out for property managers notes that there will be “No New HVAC Systems” using R‑410A after key cutover dates, even though existing systems can still be serviced. For you, that means repairs involving refrigerant top‑offs should remain possible in the near term, but you will want to weigh any major investment in an R‑410A system against the reality that the market is already pivoting to the next generation of coolants.

R‑22 and Freon: why topping off is getting so expensive

If your system still runs on R‑22, the refrigerant story is more urgent. Production of this hydrochlorofluorocarbon has already stopped, and the only legal supply now comes from reclaimed or stockpiled material. That scarcity shows up directly on your invoice: one national cost breakdown pegs the average price of R‑22 between $90 and $150 per pound, with some homeowners paying closer to the top of that range as supplies tighten. When you consider that a typical residential system can hold several pounds, a simple leak repair can quickly rival the cost of a down payment on a new unit.

Service pricing data for a home AC recharge shows how stark the gap has become between old and newer refrigerants. One estimate lists R‑410A “Freon” recharges for systems installed after 2009 in the $100 to $320 range, while R‑22 “Freon” costs are driven higher as the supply decreases. That is why many technicians now frame a major R‑22 leak as a tipping point: you can keep paying premium prices for a shrinking pool of refrigerant, or you can redirect that money into a replacement that uses safer R‑410A or one of the new low global warming potential blends.

New refrigerant families and why “low GWP” matters

The refrigerants that will dominate 2026 and beyond are designed to cool your home while doing less damage to the climate. Industry roadmaps describe how the sector is moving toward “low‑GWP” options, a shorthand for lower global warming potential, under federal climate policy. One technical overview of The Refrigerants of 2026 explains that the refrigeration industry is approaching a major transition “Under the American Innovation” in Manufacturing Act, which is the law driving the hydrofluorocarbon phase down in the United States.

For you, the jargon boils down to a few practical points. New systems are increasingly charged with blends like R‑32 or R‑454B that deliver similar or better performance than R‑410A while cutting their climate footprint. Consumer‑facing explainers on “Goodbye Old Refrigerants, Hello Earth Friendly Coolants The” highlight how the AIM Act and the Kigali Amendment are squeezing out older blends in favor of coolants that can deliver cleaner air and smaller electricity bills. When you see “low‑GWP” on a spec sheet, it is a signal that the system is built for the regulatory environment you will be living with for the next decade, not the one that is being phased out.

How new EPA tracking rules change the repair landscape

Starting in 2026, the Environmental Protection Agency is not just limiting how much refrigerant can be produced, it is also tightening how every pound is tracked. Industry guidance on How HVACR Businesses Can Prepare for the EPA notes that “Starting January” 2026, the EPA will require more detailed reporting on refrigerant purchases, usage, and leak repairs as part of a broader Refrigerant Tracking Shift. That means your contractor will spend more time logging cylinder serial numbers, job sites, and recovery volumes, and less time treating refrigerant as a commodity that can be topped off casually.

Those tracking rules sit on top of existing certification and reclamation requirements that already shape who can touch your system. Under HCFC refrigerant listings that reference EPA Section 608, only technicians with Section 608 certification can handle certain refrigerants, and many products are labeled for “service and maintenance only” with “Limited” availability. As tracking tightens, you can expect fewer gray‑area practices like venting or unrecorded top‑offs, and more emphasis on fixing leaks properly or replacing equipment that cannot be kept tight.

System compatibility: why you cannot just “drop in” a new refrigerant

One of the most frustrating realities for homeowners is that you cannot simply swap in a new refrigerant when the old one becomes expensive. Compressors, expansion valves, lubricants, and safety controls are all engineered for a specific pressure and chemical profile. Technical explainers on Broader System Compatibility and New refrigerants stress that new blends are not always backward compatible, and that trying to “drop in” a different refrigerant without redesigning the system can damage equipment or violate safety codes.

That is why your technician will usually steer you away from shortcuts like converting an R‑22 system to R‑410A. The pressures are different, the oil chemistry is different, and the risk of failure is high. Instead, you will be presented with a choice between continuing to pay premium prices for the refrigerant your system was designed for, or investing in a replacement that uses a refrigerant family with a longer regulatory runway. When you hear a contractor talk about “System Compatibility,” they are not being picky, they are acknowledging the engineering limits that sit behind every refrigerant label.

Key dates and rules that shape your next big decision

Even if you do not care about the policy details, the calendar still matters because it affects what equipment and refrigerant your contractor can legally offer. Consumer‑focused explainers on new air conditioner regulations describe “There have been two major” refrigerant shifts already: the “Phase 1: R‑22 (Freon) Phaseout” and the current move away from R‑410A toward “New Low‑GWP Refrigerants.” Another homeowner guide on Important Dates to Remember notes that “Any HVAC” equipment manufactured after early 2025 must use refrigerants like R‑454B or R‑32, and that some R‑410A equipment can remain on sale until January 1, 2028, as distributors work through inventory.

Looking ahead, commercial and large building owners are also facing a wave of compliance milestones that indirectly affect residential supply chains. One planning guide on Regulatory Shifts and Compliance Requirements notes that 2026 marks a pivotal year for HVAC projects, with several federal and local rules converging around low global warming potential refrigerants such as R‑32 starting January 1, 2026. Another industry explainer from AC Direct frames 2026 as The New Standard, noting that “From January” 2026, many new commercial refrigeration and HVAC systems must use “low‑GWP” refrigerants, which will gradually make older blends more niche and more expensive to support.

How to decide between repairing and replacing in 2026

When your AC fails in the middle of a heat wave, you care less about policy acronyms and more about whether to fix what you have or start over. The right answer depends on your refrigerant, the age of your system, and how the new rules affect long‑term costs. If you own a relatively young R‑410A system with a minor leak, a repair still makes sense, especially while service refrigerant remains widely available. If you are nursing a 20‑year‑old R‑22 unit that needs multiple pounds of refrigerant at R‑22 prices that prompt experts to say “Start planning now”, replacement is usually the more rational move.

New equipment decisions in 2026 also have to account for efficiency standards and refrigerant availability, not just upfront price. Buying guides stress that Buying an air conditioner in 2026 is different from even a year ago, because new SEER2 efficiency rules and refrigerant changes have reshaped what is on the market. Another homeowner‑oriented overview on What to know about refrigerants points out that keeping a system that uses an older blend might feel cheaper in the short term, but replacing it sooner rather than later could save you money once you factor in rising refrigerant costs and the risk of future restrictions.

Practical steps you can take now

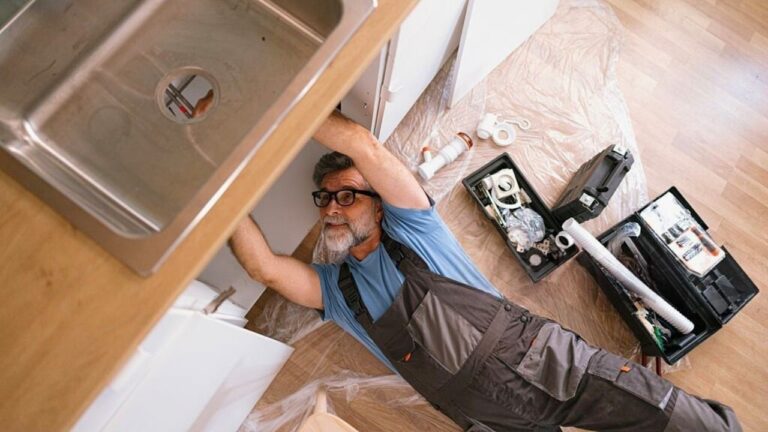

You do not need to become an HVAC engineer to navigate the 2026 refrigerant shift, but a few concrete steps will put you in a stronger position. Start by checking the nameplate on your outdoor unit or air handler to confirm whether you are dealing with R‑22, R‑410A, or a newer refrigerant like R‑32. Then, schedule a maintenance visit before peak season so a certified technician can check for leaks, clean coils, and verify charge levels, which reduces the odds that you will need an emergency refrigerant top‑off at the worst possible time. If you are sitting on an R‑22 system, ask for a frank assessment of its condition and how much refrigerant it typically needs each year.

From there, you can map out a plan that fits your budget and risk tolerance. If replacement is on the horizon, look for equipment that uses low global warming potential refrigerants and meets current SEER2 standards, and ask your contractor how the 2026 HVAC rules affect available models. If you decide to keep an older system running, budget for higher refrigerant costs and make leak prevention a priority. Either way, remember that only technicians with the right credentials can legally handle many refrigerants, which is why product listings for R‑22 “product” emphasize that they are for EPA Section “608” certified service and “Limited” availability. Your AC can still run fine in 2026, but the smartest repairs will be the ones that account for where refrigerants are headed, not just where they have been.

Like Fix It Homestead’s content? Be sure to follow us.

Here’s more from us:

- I made Joanna Gaines’s Friendsgiving casserole and here is what I would keep

- Pump Shotguns That Jam the Moment You Actually Need Them

- The First 5 Things Guests Notice About Your Living Room at Christmas

- What Caliber Works Best for Groundhogs, Armadillos, and Other Digging Pests?

- Rifles worth keeping by the back door on any rural property

*This article was developed with AI-powered tools and has been carefully reviewed by our editors.