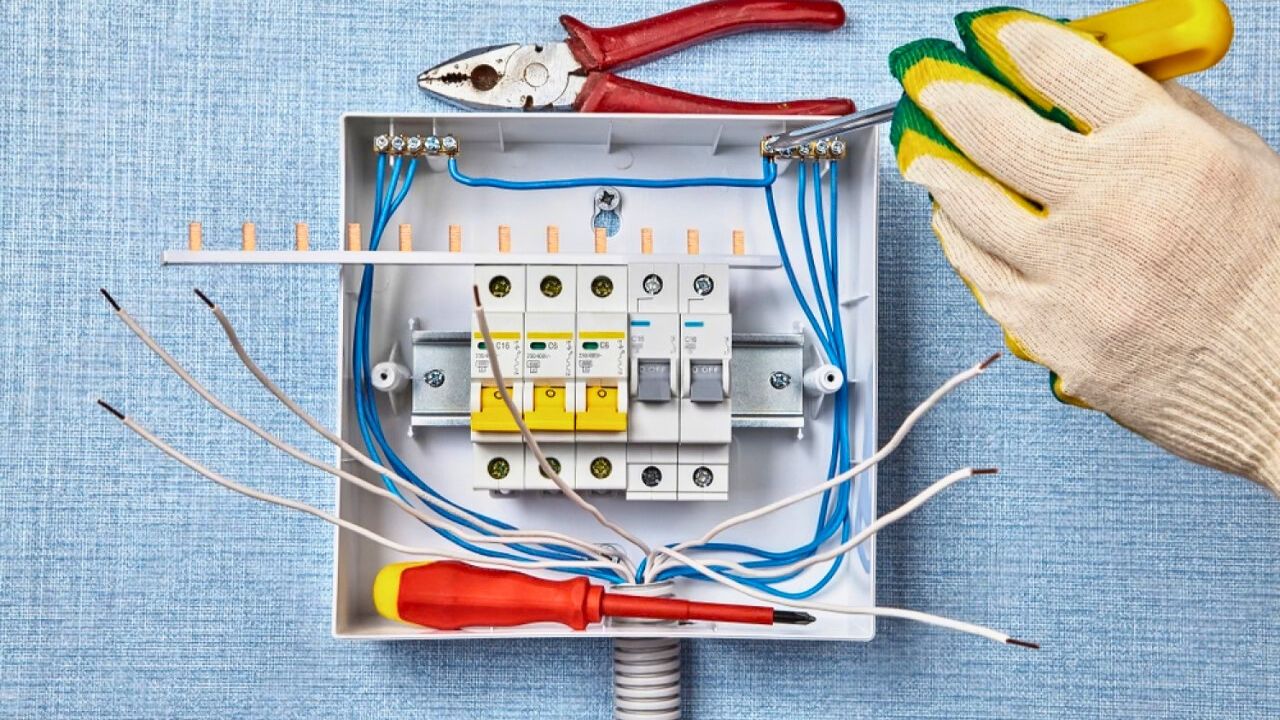

The electrical “tidy up” that creates a code problem by accident

You tidy a panel, bundle loose cables, or cram one more splice into a junction box, and the work looks sharper than what you started with. Yet that same “cleanup” can quietly push you out of compliance and into real fire risk. The gap between neat and safe is where many accidental code violations live, especially when you are not working with the National Electrical Code every day.

If you want your electrical work to pass inspection and protect the people living with it, you have to think beyond appearances. That means understanding how heat, space, and ratings interact, and how a cosmetic improvement can turn into a hidden problem the moment you tape, zip‑tie, or overfill one connection too far.

When neat turns into noncompliant

From a distance, a bundle of perfectly parallel cables or a junction box packed flush with the wall can look like the mark of a pro. You might be tempted to pull scattered runs tight, tape them together, and tuck every spare inch into the nearest box so nothing dangles. The trouble is that the Introduction to modern ampacity rules is built around how conductors shed heat, not how pretty they look, and bundling changes that physics in ways you cannot see.

Once you group multiple current‑carrying conductors together, you change their ability to cool, which is why the same guidance explains that when more than three conductors share a raceway or bundle, you have to apply When Bundling Becomes a Violation and reduce their allowed ampacity under NFPA 70. In practice, that means your tidy cluster of cables can turn a code‑compliant 20‑amp circuit into one that is effectively undersized for the breaker protecting it, even though nothing about the installation looks sloppy or obviously unsafe.

The hidden heat in bundled cables

Heat is the currency of electrical safety, and bundling is a direct way to spend more of it than you realize. When you pull several nonmetallic cables tight and tape them together for a long run, each conductor is now sharing its warmth with its neighbors instead of the surrounding air. Section 334.80 of the National Electrical Code is explicit about this for nonmetallic sheathed cable, because the plastic jackets and insulation are only tested to handle certain temperatures before they start to soften, carbonize, or crack.

Real‑world measurements back up the concern. In a technical SUMMARY of bundled conductors in bored holes in Las Vegas, researchers documented elevated ambient temperatures around grouped cables that would not exist if those same runs were spaced apart. Add in the fact that the The NEC (National Electrical Code) treats bundled conductors differently once they exceed three current‑carrying wires, and you can see how a cosmetic decision to tape everything into one tight harness can quietly push your installation into a derating zone you never calculated.

Box fill: the “tidy” mistake inspectors spot first

Junction boxes are another place where a cleanup can backfire. You might open a box, see a tangle of wirenuts and pigtails, and decide to shorten every conductor and pack the splices tightly so the cover sits flat. The problem is that the NEC uses strict volume calculations to decide how many conductors, devices, and clamps can legally live in a given box, and stuffing everything in until it barely closes is a classic red flag. Guidance on Overfilling Electrical Boxes is blunt about the stakes, describing an overfilled box as a fire waiting to happen because of the heat and mechanical stress it creates.

Professional discussions around section 314.16 of the NEC, shared among Information by Electrical Professionals for Electrical Professi, highlight how easily you can cross the line by ignoring box volume or leaving covers off after a rushed repair. Other safety guidance on Overstuffing electrical conductor boxes notes that, According to NEC rules, exceeding the calculated capacity is a common NEC violation, not an edge case. When you “tidy” by cramming more into the same space, you are not just bending a paperwork rule, you are creating a point of concentrated heat and abrasion that can fail years later.

Why “neat wiring” culture can mislead you

Social media is full of immaculate panels and cable trays, and it is easy to internalize the idea that the neatest layout is automatically the safest. In low‑voltage circles, you will even see posts insisting that “Neat wiring isn’t just beautiful, it is true professionalism,” a sentiment shared in one Neat wiring discussion. There is truth in that, because disciplined routing and labeling make troubleshooting safer and faster, but the aesthetic can also push you toward tight bundles, sharp bends, and overfilled raceways that look great in a photo and fail quietly in service.

Inspectors who walk into homes after a wave of DIY upgrades see the downside of this culture. Reporting on the home‑safety red flag that keeps showing up in “simple” fixes describes how swapping an outlet, adding a light, or extending a circuit can hide code violations behind a clean‑looking device. You might match the visual style of a professional panel while missing the calculations, derating, and box‑fill rules that make that panel safe. The result is work that passes the Instagram test but fails the first time someone opens a junction box with a codebook in hand.

Real‑world examples of “tidy” bundling gone wrong

Ask working electricians about bundling and you will hear the same story in different forms. Someone straps a dozen cables together along a basement joist, or tapes a thick bundle through a top plate, and the installation looks organized compared with the original mess. In one discussion, a commenter named Travis May is told flatly that There is no cap to how many wires can be bundled, but they can only be bundled for 24” max, a reminder that length and conductor count both matter when you pull everything into one tight group.

That same 600 mm, or 24 in, limit shows up in a separate exchange where someone asks “Is this ok?” after bundling multiple cables through framing. The response is blunt that You cannot have that many bundled for longer than 600 mm (24 in), and that Through the top plate is ok only if the grouping is short enough to avoid derating issues. These are not obscure edge cases, they are the kind of “tidy up” choices you face any time you run several new circuits to a subpanel or add multiple home‑office outlets on one wall.

Box overcrowding: when “just one more splice” is too many

Inside boxes, the same instinct to make everything fit can lead you into trouble. A popular how‑to video that warns “STOP STUFFING BOXES!” shows a scenario where three‑way switches share a box with several feeds and travelers, and the installer keeps adding conductors until the space is clearly overloaded. The host in that Nov walkthrough points out that once you exceed the calculated capacity, you are not just making it harder to fold wires back, you are violating code and increasing the chance of damaged insulation or loose connections.

Another Nov explainer on electrical box overcrowding underscores that an overfilled box presents a significant safety concern because of overheating and the potential for arcing faults. When you push conductors and wirenuts in with force so the cover will close, you are effectively grinding insulation against sharp edges and device screws. That might not fail on day one, but over time, vibration, thermal cycling, and minor movement can expose copper and create a fault path that did not exist when you first “tidied” the box.

How the National Electrical Code actually treats bundling

If you want to clean up wiring without creating problems, you have to internalize how the National Electrical Code thinks about grouped conductors. For nonmetallic sheathed cable, section 334.80 is the anchor, and a dedicated Aug training video on the National Electrical Code walks through how bundling NM for more than a short distance triggers ampacity adjustments. The key idea is that the code is not trying to stop you from organizing your work, it is forcing you to account for the extra heat that comes from multiple loaded conductors sharing the same limited airspace.

The same logic applies to metal‑clad cable. Another Aug breakdown of how the National Electrical Code, or NEC, treats MC cables explains that the NEC generally prohibits long runs of tightly bundled multiconductor MC without derating. When you combine that with the social media reminder that the National Electrical Code does not set a hard cap on bundle size but does require derating when conductors cannot dissipate heat properly, you start to see the pattern. The code is less concerned with how many zip ties you use and more concerned with how long and how tightly you group current‑carrying conductors without adjusting their protection.

Why these “small” violations matter for fire safety

It is tempting to treat bundling and box‑fill rules as paperwork details, especially when nothing trips and no one smells burning insulation. Fire science says otherwise. When a circuit is overloaded or a conductor is undersized for its actual operating temperature, Such a current could easily heat up the wires so much that their insulation melts, as one Such explanation of protective devices puts it. If that situation is allowed to develop further, the same source notes, they could easily cause a house fire, especially in concealed spaces where smoldering can go unnoticed.

Overcrowded boxes and long bundles accelerate that process by trapping heat and concentrating mechanical stress. Guidance on According to NEC code 314.16, overstuffed conductor boxes are a common NEC violation precisely because they are so easy to create during a quick repair. Combine that with the elevated temperatures documented in Las Vegas structures when cables are grouped in bored holes, and the risk picture sharpens. What feels like a minor shortcut in a single box or stud bay can become the weak link that fails under a space heater load or a summer heat wave years later.

How to clean up your wiring without creating a code problem

You do not have to choose between a rat’s nest and a violation. The safest path is to treat neatness as the final polish after you have done the math. That means checking box volume before you add another splice, counting current‑carrying conductors before you tape a bundle, and using larger boxes or additional junction points when your layout starts to feel cramped. Training aimed at Proper bundling practices emphasizes planning conductor routes so they share space without exceeding the thresholds that trigger derating or box‑fill violations.

When in doubt, err on the side of space and separation. Use stackers or individual staples instead of long continuous tape wraps, keep bundled sections as short as practical, and choose deeper or larger boxes when you know multiple cables and devices will converge. Visual discipline still matters, and the culture that celebrates straight, labeled runs has real value, but it should sit on top of a foundation of code literacy rather than replace it. If you treat every “tidy up” as a chance to revisit 314.16, 334.80, and the relevant derating tables instead of just an opportunity for nicer photos, your work will not only look professional, it will stand up to the inspector and, more importantly, to time.

Like Fix It Homestead’s content? Be sure to follow us.

Here’s more from us:

- I made Joanna Gaines’s Friendsgiving casserole and here is what I would keep

- Pump Shotguns That Jam the Moment You Actually Need Them

- The First 5 Things Guests Notice About Your Living Room at Christmas

- What Caliber Works Best for Groundhogs, Armadillos, and Other Digging Pests?

- Rifles worth keeping by the back door on any rural property

*This article was developed with AI-powered tools and has been carefully reviewed by our editors.