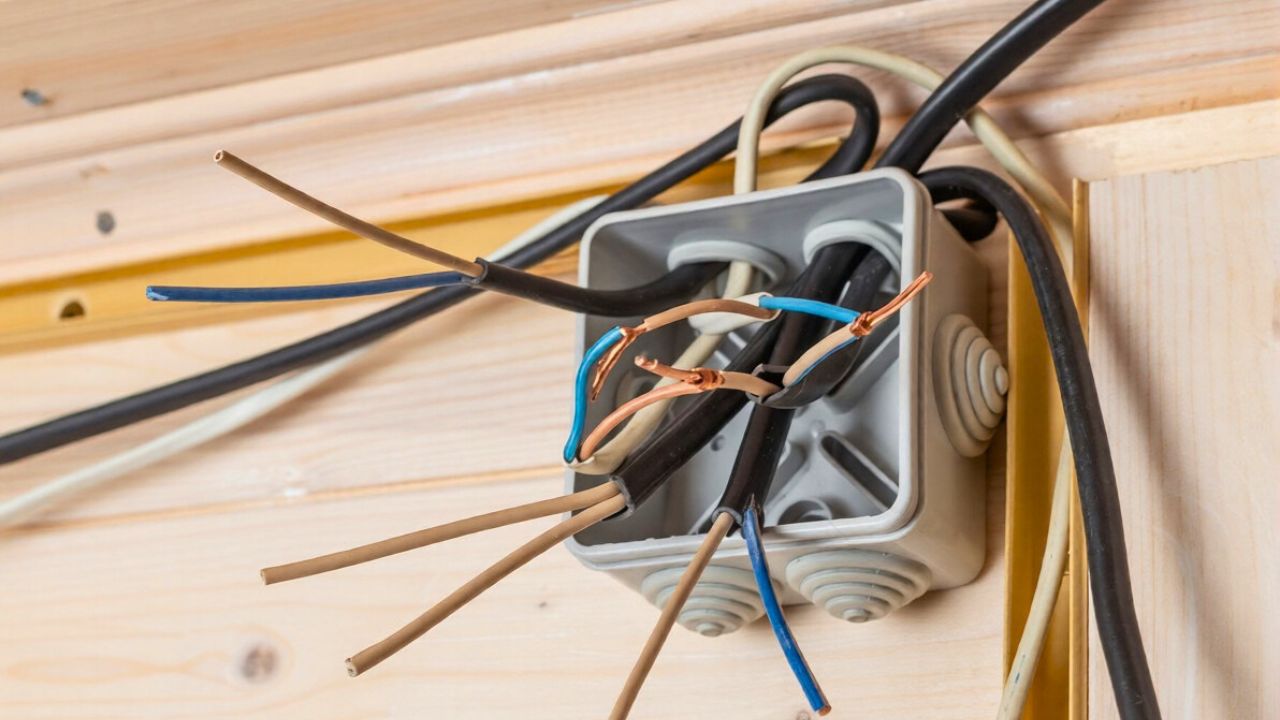

The junction box issue that turns a small repair into a bigger one

When you open a wall expecting a quick electrical tweak, the junction box is often the detail that quietly turns a simple job into a sprawling repair. A box that is the wrong size, buried behind drywall, or surrounded by a sloppy cutout can force you into patching, rewiring, and sometimes even opening more of the wall than you planned. If you understand why the codes treat these little metal and plastic rectangles so seriously, you can keep your next “small” project from snowballing into a bigger, more expensive one.

The core problem is that junction boxes sit at the intersection of safety, code compliance, and finish work, so any mistake tends to echo in all three. A box that is not accessible, not sized for the conductors it holds, or not properly supported can violate the National Electrical Code, undermine fire protection, and ruin the clean lines of your finished surfaces. The good news is that once you see how these issues connect, you can plan your work so that the box supports your project instead of sabotaging it.

Why accessibility rules can blow up a “quick” repair

Most homeowners discover the importance of accessibility only after they uncover a junction box that someone buried behind drywall or tile. The National Electrical Code treats that as more than a nuisance, because you are supposed to be able to reach every splice for inspection, maintenance, or future changes. Code language on Boxes, Conduit Bodies, and Handhole Enclosures to Be Accessible makes clear that you cannot hide these components where no one can reasonably get to them, which is exactly what happens when a remodeler tapes and muds right over a cover plate.

Once you discover a concealed box, the “small” repair you planned often turns into cutting back finished surfaces so the box can be exposed again and properly covered. Guidance on Relevant NEC Articles and Sections highlights that Article 314 and Article 300 work together to require that junction points remain reachable, with 314.29 specifically calling out accessibility for future inspection or maintenance. If you inherit a hidden box, bringing it back into compliance can mean patching and repainting, or even rerouting conductors to a new, legal location, which is why accessibility mistakes from years ago keep inflating today’s repair bills.

The specific code sections that quietly drive your layout

Even if you never plan to sit for an electrician’s exam, it helps to know which code numbers are silently shaping your project. Article 314 governs boxes, conduit bodies, and fittings, while Article 300 covers general wiring methods, and together they dictate where you can place a junction box, how large it must be, and how it must be supported. A detailed breakdown of What We Cover in these rules points to Article 314, Article 300, and the way they interact, so your “simple” light swap does not quietly violate a spacing or fill requirement.

Within that framework, several subsections matter directly to your repair. Section 314.20 of the National Electrical Code Article addresses how boxes, conduit bodies, and fittings must be installed relative to the finished surface, which is why a box that sits too far back or too far forward can trigger both safety and cosmetic problems. Section 314.28 focuses on Material and construction, specifying what junction boxes can be made of and how they must be labeled, while 314.29 requires that Boxes, Conduit Bodies, and Handhole Enclosures be accessible. When you understand that these numbers are not abstract but directly control where your box can live and how it must appear at the wall surface, you start to see why a misaligned or undersized box can ripple through the rest of the job.

How a buried or “lost” box multiplies the damage

When a junction box disappears behind new drywall or cabinetry, the problem is not only that you cannot reach the wires. A hidden splice can overheat without anyone noticing, and if a fault develops, you have no obvious access point to investigate, which is why 314.29 has been in place for years to keep electrical components reachable. One explanation of the National Electrical Court language on 314.29 emphasizes that the rule is about both safety and practicality, since a box that no one knows is there cannot be inspected or serviced.

Once you discover a concealed junction, you are often forced into a chain reaction of repairs. To comply with the requirement that Boxes, Conduit Bodies, and Handhole Enclosures Be Accessible, you may need to cut open finished walls or ceilings, extend conductors to a new box in a reachable location, and then patch the surfaces you disturbed. What started as a fixture replacement can quickly involve drywall work, repainting, and sometimes even retiling, which is why electricians are so blunt about never allowing a junction box to be covered in the first place.

Oversized cutouts: the cosmetic problem that becomes structural

Even when a junction box is perfectly legal and accessible, the hole around it can cause its own trouble. If a drywall cutout is too large, the device yoke and cover plate may not fully bridge the gap, leaving ragged edges that crack, collect dust, and draw the eye every time you walk past. Practical guides on how to fix an oversize electrical box cutout point out that a sloppy opening can ruin an otherwise clean taping job, especially when the surrounding wall is smooth and painted in a light color.

Once the cutout exceeds the footprint of a standard cover plate, you are often forced into more invasive solutions. One option is to use specialty repair rings or oversized plates, but if you want a seamless look, you may end up patching the drywall, reestablishing a tight opening, and then repainting a larger section of the wall. A step by step explanation that begins with the Introduction makes clear that the goal is to restore the structural integrity of the wall surface so the box is properly supported and the finish work hides the repair, which is more work than most people expect when they first see a slightly too big hole.

Old work boxes and the headache of oversized holes

Remodel, or “old work,” boxes are supposed to make retrofits easier by letting you cut a precise hole and clamp the box to the drywall. In practice, you often inherit openings that are too large or irregular, especially in older homes that have seen multiple rounds of DIY work. One discussion of Replies to a remodel box problem notes that Old work boxes are always a PITA, and that even when the box itself is sound, an oversized hole can leave it loose or unsupported, which is both a code and safety concern.

When the wall opening is too big for the box’s clamps to bite, you may have to sister in blocking, switch to a different style of box, or patch the drywall and start over. Some installers try to bridge the gap with joint compound alone, but that does not provide the solid backing that electrical boxes need. Advice that a 16″ span of backing should be large enough to stabilize a repair underscores how a seemingly minor sizing issue can force you into carpentry work before you can even think about pulling new conductors or installing a device.

Box size, wire fill, and why “standard” is not always safe

Another way a junction box turns a small job into a bigger one is when you discover that the existing box is simply too small for the number of conductors inside. The National Electrical Code uses volume calculations to limit how many wires, splices, and devices can occupy a given box, and if you add even one more cable to an already crowded space, you can cross the line into a violation. A list of Common Junction Box highlights Using the Wrong Size Box and Failing to Secure the Box Properl as two of the most frequent errors, both of which can force you to replace the box entirely when you thought you were just adding a new connection.

The temptation to rely on whatever “standard” box is on the shelf can be strong, but that habit often backfires. One renovation warning points out that smaller junction boxes can actually be more expensive and that choosing them poorly can create visible bulges or shadows in smooth walls, especially when you are chasing a high end finish. A detailed account that begins with “But the thing is that the smaller junction boxes seem to be more expensive” underlines how aesthetics and cost intersect with code, so you need to size boxes not only for wire fill but also for how they will sit in the wall and under the final finish.

Short wires, extensions, and the risk of compounding mistakes

Even when the box itself is sound, the conductors inside can create their own complications. If the existing wires are too short to reach a new device or to be safely spliced, you may be tempted to stretch or bend them aggressively, which can damage insulation or create unreliable connections. Practical demonstrations of how to deal with really short wires in a junction box show that you often need to add pigtails or use listed connectors to extend the conductors, which can increase the number of splices and push the box closer to its fill limit.

Once you start adding extensions, you may discover that the original box no longer has enough volume for the extra connectors and insulation. That can force you to swap in a deeper or larger box, which in turn may require enlarging the wall opening and repairing the surrounding surface. Guidance on Dangers of Incorrectly a Junction Box For example notes that overfilling a box with too many conductors or connectors can lead to overheating and even an electrical fire, so the safe fix for short wires often involves more extensive work than simply adding a few inches of copper.

Material, labeling, and why the box itself may need replacement

Sometimes the junction box problem is not its location or size but the box itself. The code is explicit that enclosures must be made from suitable materials and, in many cases, must be marked or labeled for their intended use. Section 314.28, referenced in a guide to NEC requirements, spells out how Junction boxes must be constructed and when you must label it appropriately, which means that a generic plastic container or an unmarked metal can is not an acceptable substitute, even if it seems to hold the wires just fine.

When you open a wall and find a non listed enclosure or a corroded metal box, you cannot simply ignore it and move on with your planned repair. Replacing the box with a properly rated and labeled enclosure may require loosening cables, adjusting conduit, or even opening more of the wall to provide the necessary working space. That extra effort is not cosmetic; it is about ensuring that the box can contain faults, protect conductors from damage, and provide a safe environment for splices over the long term, which is why material and labeling rules are treated as core safety requirements rather than optional upgrades.

Planning ahead so a junction box stays a small job

If you want your next electrical tweak to stay small, you need to treat the junction box as a planning priority rather than an afterthought. Before you cut into a wall or ceiling, think through where the box will sit, how it will be supported, and whether it will remain accessible under the finished surface. Reviewing the expectations in Article 314 and Article 300, including the accessibility mandate in 314.29 and the installation details in 314.20, helps you choose locations and box types that will not force you into later demolition just to satisfy the requirement that every splice be reachable for inspection and maintenance.

Like Fix It Homestead’s content? Be sure to follow us.

Here’s more from us:

- I made Joanna Gaines’s Friendsgiving casserole and here is what I would keep

- Pump Shotguns That Jam the Moment You Actually Need Them

- The First 5 Things Guests Notice About Your Living Room at Christmas

- What Caliber Works Best for Groundhogs, Armadillos, and Other Digging Pests?

- Rifles worth keeping by the back door on any rural property

*This article was developed with AI-powered tools and has been carefully reviewed by our editors.